Last week, I traveled to Duke University to conduct archival research for the second chapter of my dissertation, which investigates how the figure of the Chinese coolie and the history of the coolie trade could reconfigure the spatiotemporal dynamics of the construct “Asian America,” including questions around diaspora and memory. This chapter engages explicitly with Patricia Powell’s The Pagoda (1998), a novel that relates the story of a queer female coolie struggling to cope with a racist colonial system in nineteenth century Jamaica. In order to further contextualize my reading of the novel and to enhance my capacity to approach questions about the practice of archival research and knowledge production, I decided to visit the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library. The main collection I researched was the “Ballard’s Valley and Berry Hill Penn Plantation Records, 1766-1873,” which consists of account books, ledgers, and papers for a plantation in St. Mary’s Parish, Jamaica.

Working with the Ballard’s Valley records this summer was my first experience handling archival materials so it took me a while to get adjusted, but the staff at the Rubenstein Library was incredibly patient and helpful in terms of explaining the proper procedures and numerous do’s and don’ts for working with fragile documents.

One of the challenges I wasn’t prepared for was the difficult process of deciphering the handwritten letters between the plantation owners and managers. Since this correspondence, which documents the transition from slave to coolie labor on the plantation was the main reason for my visit, I realized that the bulk of my time in the archives would be spent training myself to read these letters, to try to make sense of what was actually written, but also to learn how to read between the lines and recognize what remains unaccounted for and unsaid.

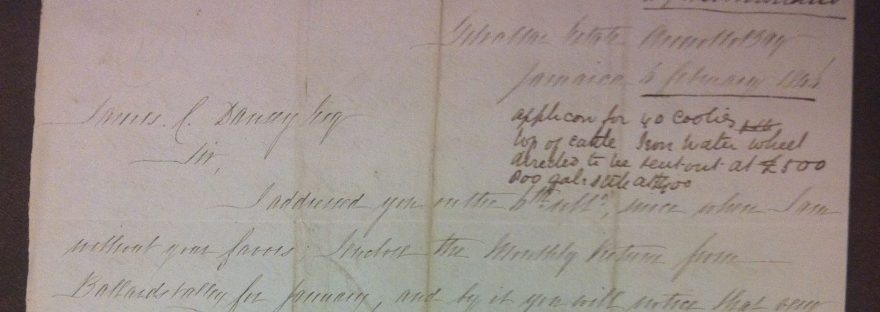

In my first few hours in the library, I struggled with a jumble of emotions, wavering between frustration, despair, and boredom as I waded through letters about drought, stock, sugar, and cattle, until I finally happened upon a notation for “40 coolies” scribbled in the upper-right hand corner of a letter dated February 6, 1846. I remember feeling disbelief and uncertainty as I wondered if the handwritten script actually spelled out the word “coolies,” or, if it was just my own wishful thinking. But this led me to read further and to go back and reread letters that I had overlooked until I found more proof that my first impressions were correct- that I had indeed come across one small, yet important piece of the history of coolie labor in Jamaica. After this discovery, I was energized and excited to delve back into the archival documents, happy to realize that I could read these letters better than I had previously thought.

An important lesson I learned while working with these materials was to open myself to the fluidity of the categories and labels that these owners and managers used, recognizing the moments when they shifted from the language of “coolies” to “East Indian immigrants” and, similarly, when “slaves” became “apprentices” after the British abolished slavery in the colonies.

Although I still have a lot of photographed letters and account book and ledger pages to decipher, this has been an eye-opening trip, not just because of the material documents I was able to engage with, but the experience of learning how to navigate and work in an archive. I’m sure it will be a skill I continue building upon in the years to come. A big thanks to the Advanced Research Collaborative at the Graduate Center, CUNY for the grant that made this all possible!

That’s all for now- more updates to come as I continue to decode these letters and, of course, figure out how they will fit into my second chapter.

Image features a letter from Henry Westmorland, Ballards Valley, to James Dansey, London, February 6, 1846 from the “Ballard’s Valley and Berry Hill Penn Plantation Records, 1766-1873” at the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library.